Last week, on September 1st, UMass Amherst resumed in-person instruction for the Fall 2021 semester. While I, of course, had some trepidation about having 300 people in a large lecture hall with the Delta-variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus circulating widely, I cannot describe how happy I am to return to the classroom. In addition, the restoration of in-person instruction after such a long hiatus offers new opportunities for what I consider to be one of the most important goals of the first few meetings of any course: breaking expectations.

After teaching completely remotely for the past year, plus the end of Spring 2020, seeing students’ faces really is a relief. I hated teaching online. I missed the feedback I get from folk’s faces. Teaching to a field of black boxes with names on them is just not the same. I also missed the casual interactions before and after class as well as the chance meetings in the hallways. Even though I tried to begin most every remote class with casual conversation about my students, it is not the same as being able to smile (even behind a mask) and say hello to people as I walk around the room.

Our collective long separation from the classroom, however, does bring a unique opportunity: to carefully reconsider how we as instructors establish the climate for our classrooms. All students come in to any class with expectations of what the course will entail. In a physics course, our cultural zeitgeist suggests that students will spend their time listening to a boring old white guy drone on-and-on lecturing at them as to which formula they should use in a given problem. In this mental picture, students are passive and not truly thinking about how physics connects to their interests or how it applies to the “real world.”

While I cannot help the fact that I am turning into an old white guy one year at a time, I can do my best to break these other expectations on the first day. In my view, such a breaking of expectations is the key aim of the first day’s class. Through activities which actively engage students with the material on the first day, as opposed to simply lecturing on the syllabus, students learn that this course will not be active lecture. I also strive to connect the material to fields that, at first, seem wildly remote from physics: art, philosophy, literature, biology, history, and dance, for example.

Making such connections serves two important functions. The first of which is that these connections humanize me as an instructor; they show that I have other interests beyond physics. Due to unfortunate shows like The Big Bang Theory, many students are actually surprised by a physicist with multiple dimensions even though many real physicists have a variety of other interests. Furthermore, by showing my own humanity, I hopefully create a more inclusive classroom community. I am saying, “Look, I have interests beyond physics, and am welcome here. I want you, with all your interests to be welcome here too.”

The second important reason to spend part of the first day connecting physics to other fields is to bring physics back to reality. So many students, and people in general, feel that physics is detached and remote. Connecting it to other fields makes it less intimidating and more relatable.

So how do I do this? Using Physics 132 – Introductory Physics for Life Sciences II: What is an Electron? What is Light? as an example

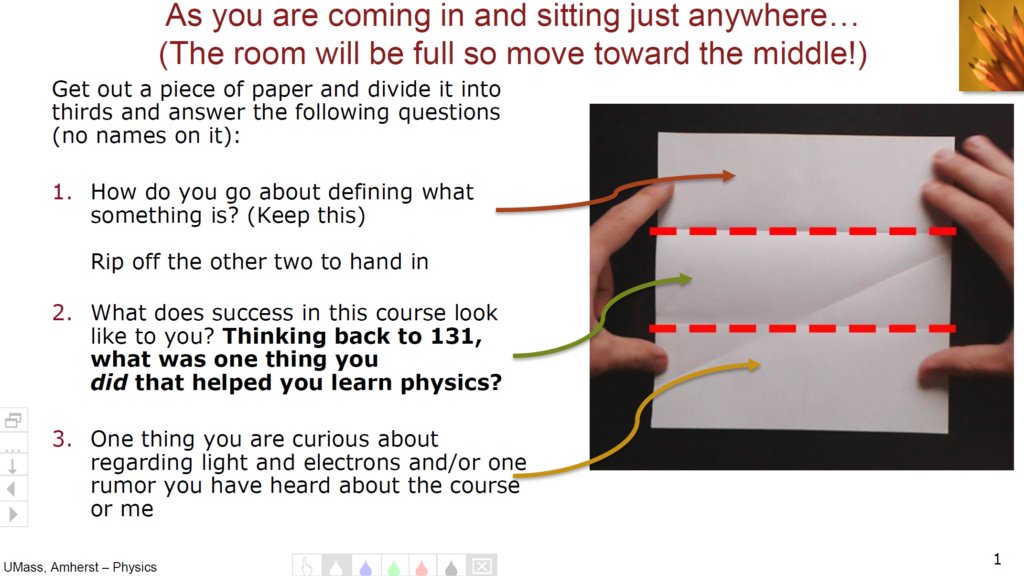

In this course, I begin the first day’s class with an exercise based upon a Hopes and Fears activity I learned from Dr. Helmer as part of my Teaching for Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity Ambassadorship. Students take a piece of paper and divide it into thirds and answer the following questions:

- How do you go about defining what something is?

- What does success in this course look like to you? Thinking back to Physics 131, what was one thing you did that helped you learn physics?

- One thing you are curious about regarding light and electrons and/or one rumor you have heard about the course or me.

These instructions are up on a slide as the students are coming in. Then in the pre-class time and the first minute or so of class, myself and the TAs go around the room collecting the answers to questions 2 and 3, and, at the same time, giving myself and the teaching team a chance to get to know students in a one-on-one manner and begin developing the supportive rapport so critical for student success.

This activity forms a key step in breaking student expectations. Students are not expecting to think and engage as they are sitting down on the first day. Even if they are, students are expecting to maybe introduce themselves or have something about the syllabus. These three questions, in contrast, are asking students to think about:

- The fundamental guiding questions of the course in a non-physics/philosophical context.

- Their own learning and what was successful in the past.

- Their own curiosity.

I then use these responses throughout the course. I keep the papers with their responses to question 3, their curiosities, for the semester. When we then cover a related topic, I put one on the document camera. Showing student interests in their own handwriting helps engagement with the material. I am saying, “y’all were interested in this, well now let’s answer it!”

Some students answer question 3 with a rumor instead. These are anonymous, so I typically get some rather candid responses like, “I have heard the 132 is harder than 131.” I can then address these comments head-on, hopefully putting students at ease and showing that I want to hear their opinions on the course.

For question 2, “Thinking back to 131, what was one thing you did that helped you learn physics?” I use the responses as a jumping off point to talk about the structure of the class. Students almost always comment that doing problems and talking about the concepts was what was helpful in their success (one of the benefits of a large class is that, due to statistics, it becomes very easy to predict what will be said!). I can then say, “OK, so doing problems and talking to peers helped you learn phyics. In that case, let’s do problems and talk to peers in class!” This provides an excellent source of buy in for the creation of an active learning classroom with preparatory homework.

Finally, the philosophical question 1 provides students a chance to think about, frankly, rather difficult ontological question before conversing with their peers. We then revisit this question as a class later in the first day: again talking about non-physics related topics. I ask them to worth with their peers to come up with a list on a small whiteboard (about 2ft x 3ft) which they then hold up. Again, the active engagement sets a key tone for the rest of the class; it says, “this is what we will be doing!” Moreover, through this process, the students themselves discover some of my goals for the class: the importance of multiple representations, for example. However, now the goals are not coming from me, but from the students themselves, which can be empowering for the students.