Introductory Physics for Life Sciences

In addition to answering the fundamental question “What is Physics?”, which, I think all introductory physics courses should answer, Physics 131 also strives to make the course

- Interesting

- Relevant

- Authentic

for the biology and other life-science majors who comprise the population of this course. To achieve this end, I follow the lead of other pioneers in this space such as Redish & Crouch and ask the following critical questions:

- Why are we covering this material?

- Why is it relevant for this population?

- How does it support/enhance the material they are learning in their major courses?

- What order of presentation makes sense for these students?

In all cases, following the lead of the Chemical Thinking Curriculum at University of Arizona, I have elected to go for depth over breadth.

Our Topics & Order

Unit I: Entropy

Entropy may seem like an odd place to start. After all, almost all introductory physics curricula begin with considerations of position, velocity, and acceleration. Even those that do follow alternative orders, such as di Sessa, begin with some other topic common to introductory physics such as momentum.

Our critical questions, however, encourage us to reconsider this approach. Why do we start with the kinematic quantities and does that justification make sense in the light of our students’ interests?

I suspect that the traditional order has two justifications:

- Tradition: questions of motion go way back in natural philosophy, famously vexing the likes of Zeno of Elea, and such questions were some of the most interesting to the scientific community for millennia.

- Familiarity: I also suspect that the kinematic quantities are considered good places to start because of their fundamental connections to everyday life; Almost everyone has traveled some distance and asked “are we there yet?” which is fundamentally a question about space, time, and speed.

However, are these points true for the IPLS population? With regards to the first point, I would argue that the kinematic quantities are not the most interesting. Problems on kinematics, particularly problems solvable at the introductory level, are very difficult to make what Redish describes as “authentic”.

By biologically authentic applications, we mean those that use tools —such as concepts, equations, or physical tools —in ways and for purposes that reflect how the discipline of biology builds, organizes, and assesses knowledge about the world. We note that it is not only the perspective of the disciplinary expert that matters here; the student’s perception of biological authenticity matters as well. When they perceive physics as valuable to their understanding of biology and chemistry, their engagement in-creases dramatically.

E.F. Redish et al, Am. J. Phys. 82, 368 (2014).

This challenge is reflected in the Living Physics Portal where only 51 of 205 entries are kinematic in nature. I suspect that a main hurdle in achieving authenticity is the fact that essentially nothing in the life sciences moves with constant acceleration. Thus, biologically authentic problems, solvable at the algebra-based level are essentially impossible.

Entropy, by contrast, is easily connected to the life sciences. Many of the processes that students explore in introductory biology and chemistry are, at last partially, entropically driven including diffusion, and polymer folding.

In addition to being biologically relevant, entropy provides an excellent venue for discussing models. As discussed in the Modeling Instruction curriculum, model building is some thing that must be explicitly taught. One good example is oil-water separation. Essentially all IPLS students have seen this both in their everyday lives and in their into biology courses. Moreover, the complexity inherent to ~1022 molecules moving with complete freedom in 3-D space makes “selling” the need for a simplified model, such as the one below much more straight forward.

As for the second idea: that the kinematic quantities are a reasonable starting point because of their familiarity, I am not sure of this hypothesis’s validity either. As shown in the diagram above, most of our students have spent two years studying biology and chemistry at the college level before entering IPLS 1. For such students, what will be more familiar in terms of being an object of scholarly study: the kinematic quantities or energy and entropy?

Unit II: Energy

After entropy my class moves on to the study of energy. While energy is a more common topic for a first-semester physics course, I continue to follow the lead of IPLS’ pioneers like Redish & Crouch and critically consider how to make the presentation of this topic relevant to life-science students. As a result, my energy unit:

- Incorporates a large amount of material which would traditionally be included in a physics unit on thermodynamics including:

- Temperature Heat

- Thermal energy

- Chemical potential energy

- Develop a coherent picture of energy across disciplines.

Unit III: Space & Time (aka Kinematics)

After our discussions of entropy and energy, students typically take their first midterm following the protocol outlined in the section on Team-Based Learning.

Only then, early April in a spring semester, do we get to what is traditionally the first topic in an introductory physics course: the study of the kinematic variables of displacement, velocity, and acceleration.

I call the unit “Space & Time” instead of “Kinematics” for a couple of reasons. First, Space & Time” are concepts which students can already define. Second, the fact that space and time can be quite counter intuitive in modern relativistic physics has sufficiently entered the zeitgeist that enough students are excited as to be infections. In the words of one student in end-of-course evaluations,

I never expected to

learn about such fundamental

ideas as space and time in

an intro physics class!

Not only is the naming of the unit different to intrigue life-science majors, but the actual content has also been deeply reconsidered. As stated above in the discussion of the entropy unit, the traditional focus on constant acceleration is of limited utility for life-science students. Moreover, observation of students solving such constant acceleration problems reveals problem solving behaviors directly antithetical to the principles-first reasoning which is the aim of our “What Is Physics” essential question; students solve such problems by “listing equations, knowns, and unknowns followed by solving without thinking.”

Instead of such a traditional approach, I teach the mathematical study of space and time through numerical integration. As described in the section on incorporating computation, this approach has the benefit of allowing explorations beyond the constant acceleration case as well as conferring other benefits

Unit IV: Forces

Only here, at the end of the semester, do we get to a discussion of Newton’s laws. I am still, however, looking at how to make the topic relevant for life science students.

The biggest difference here, relative to a traditional course is the integration of fluid resistances throughout: both linear and quadratic in velocity as well as a consideration of the impact of Reynolds numbers.

Other Benefits of this Order

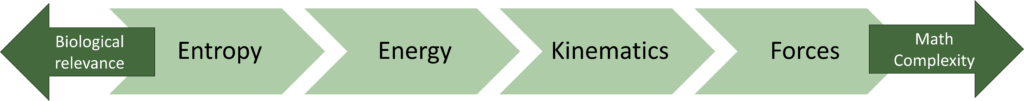

In addition to the benefits listed above, this topic order has other attributes which recommend it. First, as mentioned above, its easier to create interesting authentic examples earlier in the course this way. Furthermore, this order makes a lot of sense in terms of smoothly increasing the mathematical complexity:

- Unit I Entropy: Depends only on counting

- Unit II Energy: Depends on scalars and the more familiar quantities of distance and speed (as opposed to displacement and velocity).

- Unit III Space and Time: Now that distance and speed have been used, we can explore the distinction between these ideas compared to displacement and velocity. Moreover, while kinematics ostensibly uses vectors, once initial velocities are decomposed, the system can be mostly thought of as pairs of algebraic relationships. More sophisticated vector algebra, like addition, is not required.

- Unit IV Forces: Now, we can introduce students to the full vector arithmetic.

Bibliography

- E.F. Redish et al, NEXUS/Physics: An Interdisciplinary Repurposing of Physics for Biologists, Am. J. Phys. 82, 368 (2014).

- C. H. Crouch and K. Heller, Introductory Physics in Biological Context: An Approach to Improve Introductory Physics for Life Science Students, American Journal of Physics 82, 378 (2014).

- A diSessa, Momentum Flow as an Alternative Perspective in Elementary Mechanics, Am. J. Phys. 48, (1980).

- Workshop Physics Schneider Grinnell College, http://schneidm.grinnell.edu/~schneidm/dp.html.

- J. Jackson, L. Dukerich, and D. Hestenes, Modeling Instruction: An Effective Model for Science Education, Science Educator 17, 10 (2008).