Team Based Learning Building to a Final Projects

The fundamental principle of team-based learning is that knowledge is constructed in a social context by actually doing the discipline in teams with their peers. In order to do this, students must come to class prepared to engage in the material. They then work together during class to solve problems.

Preparation and Its Evaluation

In order to spend time during class solving problems, students must come prepared with some fundamentals.

How students are empowered to come prepared to class

In the context of our class’s fundamental questions, “What is Physics?” and “What is Math?”, this means that the physics part of the preparation is purely conceptual: with nothing the students would recognize as math. Students are expected to learn this material from a textbook; in our case, we use a free open access textbook of our own construction to make sure it both matches our course exactly and for purposes of inclusion. To help them master this material, students are expected to complete formative online homework problems in the Edfinity system with 6 attempts per problem. The total prep is about 60 pages and the homework assignments are generally about 25 problems.

Evaluation of Preparation

After completing the preparation, and before we discuss the material in class, students complete a summative assessment on their homework. The questions on this assessment are only minor adjustments to those problems students have already successfully completed. There are two different ways I have explored conducting this evaluation: a single multiple choice quiz at the start of the unit and daily quizzes throughout. In both formats, students first take the quiz individually and then the same quiz with their teams. The final grade is a 50/50 split between individual and team contributions.

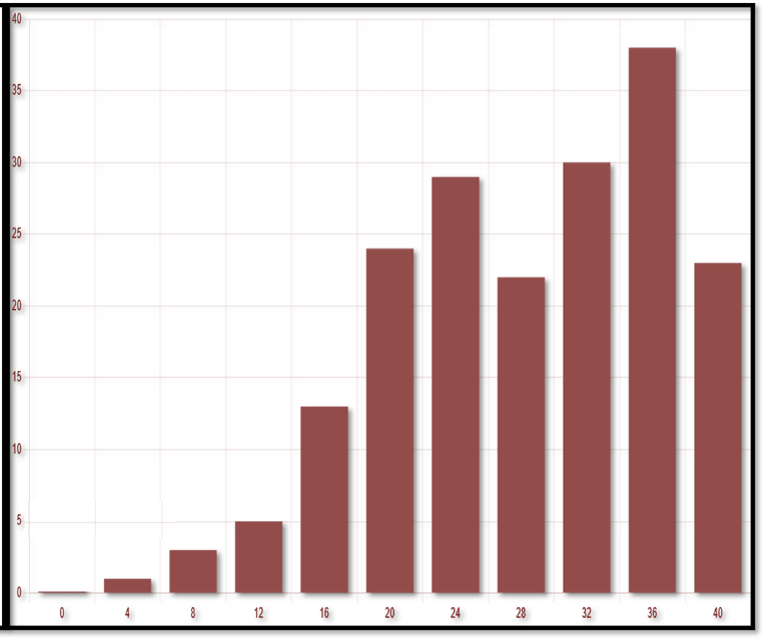

The single quiz is most in line with the readiness assessment process articulated in Michaelsen et al. In this mode, students take a 10-question multiple choice quiz. One point remarkable to us was how successful students are on these quizzes as is visible in the grade distribution from the first quiz in the figure: any student in the first three bins is well on track to earning an ‘A’ with our grading scale. For the collaborative portion, students get 4 attempts per question with one point off for each attempt. Logistically, students complete the individual portion and as soon as all their teammates are done are free to go out in the hall and do the collaborative under the proctoring of a teaching assistant. The total process, individual and team, takes effectively the entire class period and thus no other activities take place that day.

The other format is daily quizzes. I have been using this format for some time in the IPLS-II course. The lecture hall in which that course is held prohibits the 10-question quiz described above: asking students in the middle of the room to just sit quietly, unable to get up, while all their peers complete the quiz. The solution is a single-question daily quiz administered through the iClicker or other audience response system. As before, students take the quiz individually and then, when everyone is complete, they collaborate and answer the question again. Also as before, the final grade is a 50/50 individual/collaborative. Such a format is more amenable to the lecture hall environment as students only need to wait until everyone finishes a single question: a much shorter period. After the subsequent collaborative quiz, the class proceeds and, as described above, the quiz question can be a step in one of the problems for that day.

In addition to practical considerations, I believe that the daily format has other benefits which is why I plan to implement it in the next round. The main benefit is reinforcing the connection between the homework and the in-class problems being done that day: the quiz can often be structured as to be a small part of one of the problems. In contrast, I have often had critiques from students using the all-at-once quiz structure that they feel that the homework is not connected to what is done in class. This critique occurs much less often with the daily structure.

The connection between the prep and class is further reinforced by the intermittent practice, advocated by Brown et al., that such a structure inherently possesses. In my implementation, students must be told which homework problems will form the basis for the next class’s quiz. My end-of-class broadcasts (discussed in the section on inclusion) include a sentence to the effect of, “you quiz for next time will be based on homework problems 2, 3, 4, and 6.” This encourages students to go back and review that material in preparation for the quiz, and consequently, the next day’s class as well in line with suggestions for just-in-time teaching as described in Novak et al. Of course, for inclusion, a certain number of dropped quizzes are required (I usually go with 4 out of the approximately 16 quizzes throughout the semester. As stated previously, I plan to implement this version in the next iteration of IPLS-I.

In-Class Activities

After the quiz (either the full day version or the in-class version), students complete in-class activities. These include: writing equations as described in the section on essential questions; doing conceptual ABCD questions as described in Ed Prather’s work; and solving in-class problems. For this last category, I will generally do an example problem and then leave it on the “jumbotron” screens while students work. This allows myself and all the TAs and LAs in the room to reference what I did in my problem and use that to help students learn to generalize from one problem to another which has significantly different surface characteristics (a term from Chi et al.).

Additional Practice

While the in-class practice alone is generally enough to do well on the exams (more on those below), they are not in-of-themselves adequate for most students to earn an ‘A’ in the class as the results of post-exam reflections (an activity which promotes inclusion through metacognition) shown below indicate. Thus, additional practice needs to be provided. My class has two different types of additional practice: Next Time Problems and Additional Practice Worksheets.

| Average Exam Score Puts Folks on Track for… | Board Work Behavior | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Writer | Contributor | Occasional Contributor |

Work Alone |

||

| Usage of Additional Practice Problems as part of studying. | Made a large part of my studying. | A | A-/B+ | B- | |

| Used some. | A-/B+ | B | B | ||

| Barely or did not use. | C | C | C | ||

None of these problems are collected or in any other way graded for a few reasons:

- These students are predominately second- and third-year students and learning to take advantage of additional resources to supplement learning is a critical skill that I am hoping to help them develop.

- The only way we could grade such problems is if they were online. However, I have observed that when students try to complete online graded homework, they often attempt to do the problems completely in their calculator without recourse to pen and paper. However, I wholeheartedly believe that most physics problems cannot be solved in this calculator-only way with reliable success.

- Grading perverts the motivation: when an assignment is graded students, understandably from an economics perspective, tend to focus on getting the correct answer which can incentivize academic dishonesty. Ungraded assignments, however, refocus the purpose on learning and improvement. This change in incentive is, of course, one of the main bases of the current interest in alternative grading as in Clark and Talbert.

NextTime Problems

These additional practice problems were developed in full by a former student of mine. NextTime problems are single problems appended to the end of each day’s slides. This problem uses the exact same skills and concepts as those done earlier in the day so that students know exactly what material to refer for help. The full worked out solution is then provided at the beginning of the next day’s slides. This delay in providing the solution provides a window where students (such as myself as a student) cannot be tempted to look at the solution too early.

Additional Practice Worksheets

Beyond these NextTime problems, I also provide worksheets of problems from commercially available banks. I simply create worksheets and then post them to my LMS. These problems have answers, but not fully worked out solutions. While students often ask for full solutions, I do not provide them explicitly because I have found that some students resort to what I call “solution collecting” thinking that if they can memorize the solution to each problem on the practice, they will then be ready for the exams. Moreover, I suspect that the students who engage in this practice may well be those who would benefit most from the struggle that Make it Stick identifies as one of the key principles of teaching. In the words of Heller and Heller’s 3rd Law of Education,

“Make it easier for students to do what you want them to do and

K. Heller, P. Heller

more difficult to do what you don’t want.”

Exams

After each two units, there is an exam. These exams are also done pyramid style (see Zipp) wherein students first take the exam individually and then take the same exam with their teams. For exams, I use a 75% individual/25% team breakdown. Also associated with each exam, students are expected to complete a constellation of various metacognitive exercises to get as much learning out of this experience as possible.

Individual Portion: Structure and Logistics

The individual portion of the exam is also hosted on the Edfinity platform. However, students generally take the exam in person in a proctored environment (though the online nature allows students with minor illness or who are traveling for sports etc. to take it remotely). There are several features of the exam administration designed for equity and inclusion. The exam is about 24 problems distributed over 10 situations (to reduce cognitive load). They include a mix of calculation, simulation, conceptual questions, and questions which require students to learn about a new physics concept and translate their observations into mathematics. Moreover, the exam is designed to take approximately one hour and all students are given two hours to do it (effectively giving all students the double-time accommodation). This last aspect is facilitated by the UMass cultural acceptance of night exams.

Collaborative Portion: Logistics

The collaborative portion can be done either immediately after the individual portion (with students hanging around until all are finished) or the next day. Both modes have their advantages and disadvantages and I have been unable to settle on which is better.

- Completing the team portion immediately after the individual exam means that students leave the exam room knowing effectively how they did.

- Completing the team portion the next day in class. This is often simpler logistically. Moreover, double time is not needed for this assignment as all groups can complete the exam within the allotted time.

Teams once again complete the exact same exam as before with 4 attempts per question. There is a deduction of 25% credit per attempt.

Teams

Throughout this discussion, there are several references to “student teams.” These are obviously a key point in the Team-Based Learning pedagogy. Students are placed in teams of five. This team size is much larger than other studio-style courses such as the SCALE-UP of Beichner et al. and the Collaborative Problem Solving method of Heller and Heller. However, the work of Kowitz and Knutson make a compelling case for this larger team size, under the assumption that the tasks students are being asked to complete are sufficiently difficult. There are several different aspects of forming and norming the teams which place inclusion at their heart.

Team Evaluation

One of the biggest concerns that all students have regarding teams is the “slacker effect” (a variation of students’ words). To mitigate this, we use the CATME system described in the paper of Ohland et al. At the end of the semester, students evaluate their teammates. The result is a multiplier which applies to all team-based assignments in the course: collaborative quizzes, collaborative exams, the metacognitive journals described in the section on Metacognition and Inclusion, and the final projects described below. The vast majority of students earn a multiplier of 1. However, grades up to 1.05 are available for those teams who feel that a singular team member when above and beyond expectations. One nice attribute of the CATME system is that it is not zero-sum: one student getting more than one does not imply that another student in the team got less than one. Moreover, experience shows that most students feel the evaluation process is fair. To help ensure this perception of fairness, we do a practice run midway through the semester providing an opportunity for students to not only get feedback but also to internalize the impact of a multiplier on their grades.

Final Projects

To help with authenticity, a concept discussed in the section on IPLS, instead of a final exam, students complete a final project based on the concepts of project-based learning in Krajcik and Blumenfeld. The students choose from a selection of projects ranging from evolutionary morphology to food science and kinesiology. The projects come with authentic data collected from biologically-related papers. Students then use the forces and kinematic data to gain deeper understanding on the projects and present them in a final poster session / oral exam.

Read More

- Overview of the Course

- Team-Based Learning Building to a Final Project

- Course Goals and Essential Questions: “What is Physics?” and “What is Math?”

- Introductory Physics for Life Sciences

- The Integration of Computation via Spreadsheets

- Inclusion and Metacognition

Bibliography

- Larry K. Michaelsen, Arletta Bauman Knight, and L. Dee Fink, Eds., Team Based Learning: A Transformative Use of Small Groups in College Teaching. Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2004.

- Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, and Mark A. McDaniel, Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning (Bleknap Press, Cambridge, MA, 2014).

- G. Novak, A. Gavrin, W. Christian, E. Patterson, and G. M. Novak, Just-In-Time Teaching: Blending Active Learning with Web Technology, 1st edition (Addison-Wesley Professional, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 1999).

- Edward Prather, Are You Really Teaching If No One Is Learning?, https://youtu.be/NCUyIh3PssI.

- M. T. H. Chi, P. J. Feltovich, and R. Glaser, Categorization and Representation of Physics Problems by Experts and Novices*, Cognitive Science 5, 121 (1981).

- D. Clark and R. Talbert, Grading for Growth: A Guide to Alternative Grading Practices That Promote Authentic Learning and Student Engagement in Higher Education (Taylor & Francis, 2023).

- Heller, Kenneth and Heller, Patricia, Cooperative Problem Solving in Physics A User’s Manual: Why? What? How?, in (n.d.).

- J. F. Zipp, Learning by Exams: The Impact of Two-Stage Cooperative Tests, Teach Sociol 35, 62 (2007).

- R. J. Beichner, J. M. Saul, R. J. Allain, D. L. Deardorff, and D. S. Abbott, Introduction to SCALE-UP: Student-Centered Activities for Large Enrollment University Physics, 2000.

- Albert C. Kowitz and Thomas J. Knutson, Decision Making in Small Groups: The Search for Alternatives (Allyn and Bacon, Inc., Boston, MA, 1980).

- M. W. Ohland, M. L. Loughry, D. J. Woehr, L. G. Bullard, R. M. Felder, C. J. Finelli, R. A. Layton, H. R. Pomeranz, and D. G. Schmucker, The Comprehensive Assessment of Team Member Effectiveness: Development of a Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scale for Self- and Peer Evaluation, Academy of Management Learning & Education (2013).

- Krajcik, Joseph S. and Blumenfeld, Phyllis C., Chapter 19: Project-Based Learning, in The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, edited by R. Keith Sawyer (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2012), pp. 317–333.